Learn how to write a witness statement template with this practical guide. Get actionable tips and a clear structure for creating legally sound documents.

A solid witness statement template is all about capturing someone's firsthand account of an event in a clear, factual way. At its core, it needs to include the witness's details, a step-by-step story of what they saw or heard, and a signed declaration that everything they've said is true. Getting this foundation right is crucial for both clarity and legal weight.

Before we get into the nitty-gritty of building a template, let's talk about why it's so important. A witness statement isn't just a piece of administrative paper; it's a critical piece of evidence that can genuinely sway the outcome of a court case, an internal HR investigation, or any formal dispute. Its entire job is to lay out a factual, believable account from one person's perspective.

Think of the template as your blueprint for getting that account right every single time. When you're dealing with multiple witnesses, using a standardized format is the only way to make sure everyone provides the same crucial pieces of information. It's your best defense against the kind of small omissions or inconsistencies that can unravel a legal argument or confuse an investigation.

A well-crafted template does more than just organize information; it guides the witness. It helps them structure their memories into a logical, chronological story, turning a jumble of recollections into a powerful narrative. The key is to keep the focus squarely on what the witness personally saw and heard, pushing speculation and opinion to the side.

Without that structure, you open the door to trouble. A witness might ramble, forget something critical, or accidentally include hearsay that gets the statement thrown out. A good template minimizes these risks by prompting for specific details in the right order:

Start your free trial today and experience the power of AI legal assistance.

3-day free trial • Cancel anytime

A strong, detailed witness statement can make a significant difference in the outcome of a case. It can support or refute the statements made by the parties involved, which is particularly important in situations where liability is contested.

Standardization isn't about bureaucracy; it's about strategy and efficiency. In a business context, having a go-to template for workplace incidents or HR complaints ensures that every report is captured with the same rigor. You see this same principle at play with things like structured case study templates, which companies use to ensure every story is told with the same clarity and impact.

A reliable template also saves an incredible amount of time. Legal professionals and investigators can hit the ground running without having to reinvent the wheel for every witness. It lets them focus on the substance of the statement—the story itself—rather than worrying about the format.

Ultimately, a great template is your first line of defense in building a credible and defensible record of what actually happened. It prevents the kind of simple mistakes that can derail an otherwise solid case.

A powerful witness statement isn't just a simple retelling of events. It's a carefully constructed document where every single part has a specific legal job to do. Getting this structure right is the first, most crucial step toward creating a template that is both clear and legally compliant.

The whole point is to build a framework that guides the witness, making sure their account is presented in a way that a court, tribunal, or investigator can easily digest and reference.

From the case details at the very top to the signature at the very bottom, each component builds on the last to establish credibility and lay out the facts in a logical, undeniable sequence. Let's walk through these essential elements.

At the very top of the first page, every witness statement needs a case caption. Think of this as the document's formal title. It immediately identifies which legal proceeding the statement belongs to, which is critical for preventing mix-ups when multiple actions are in play.

Here's what the caption must include:

Getting this right sets a formal, professional tone from the get-go and ensures the document gets filed correctly.

Right after the caption, the statement must introduce the witness. This isn't just a polite "hello"; it establishes exactly who is giving the evidence and what their relationship is to the situation. It gives the reader crucial context.

This section should clearly state the witness's:

For instance, you'll often see something like: "I, Jane Marie Doe, of 123 Oak Street, Anytown, a retail manager, will say as follows..." This simple declaration immediately grounds the statement in a real person and their background.

This is the heart of the document—where the witness lays out their account. The structure here is absolutely vital for clarity. The entire story must be broken down into sequentially numbered paragraphs. Each paragraph should ideally stick to a single, distinct point or event.

This formatting is non-negotiable. It makes the statement incredibly easy to read and, more importantly, to reference. During legal proceedings, you'll hear lawyers and judges refer to "paragraph 14 of Ms. Doe's statement" without any confusion. It keeps everyone on the same page.

A critical rule here: the narrative must be in the witness's own words and from a first-person perspective. The witness should only detail what they personally saw, heard, or did. Stick strictly to the facts—no opinions, no guessing, no conclusions.

For a deeper dive into the nuances of sworn testimony, our guide on creating a sworn statement can provide more detail.

Before we move on, let's summarize the key parts of any witness statement template. These are the non-negotiables that form the backbone of the document.

| Component | Purpose and Key Details |

|---|---|

| Case Caption | Formally identifies the legal case. Includes court name, case number, and parties. |

| Witness Introduction | Establishes the witness's identity. Includes full name, address, and occupation. |

| Numbered Paragraphs | Structures the narrative for clarity and easy reference. Each paragraph focuses on a single point. |

| Statement of Truth | A legally required declaration confirming the truthfulness of the content. |

| Signature and Date | The witness's signature and the date of signing, which formally validates the document. |

Each of these elements plays a vital role in ensuring the statement is taken seriously and stands up to legal scrutiny.

And finally, every witness statement must end with a Statement of Truth. This is the formal declaration where the witness confirms that everything they've written is true to the best of their knowledge and belief.

The exact wording can change slightly depending on the jurisdiction, but it generally looks something like this:

"I believe that the facts stated in this witness statement are true. I understand that proceedings for contempt of court may be brought against anyone who makes, or causes to be made, a false statement in a document verified by a statement of truth without an honest belief in its truth."

This declaration is what gives the document its legal weight. It’s followed by the witness’s full signature and the date it was signed. Without this verification, the document is just a story; with it, it becomes formal evidence.

Once you have the basic structure down—the caption, the numbered paragraphs—you get to the real substance: the narrative. This is where you help the witness translate a messy collection of memories into a clear, factual story that holds up under scrutiny. A compelling narrative isn't just a dry list of events; it's a firsthand account that puts the reader in the witness's shoes.

The trick is to let the witness tell their story in their own voice. You want it to sound genuine, not like a lawyer drafted it. An overly polished or "over-lawyered" statement can feel stiff and, ironically, less believable. The most powerful statements are simple, direct, and stick to what the witness personally saw, heard, and did.

Every single sentence in the body of the statement needs to come from the witness's perspective. That means using "I" throughout. The entire point of a witness statement is its directness, so the language should reflect personal observation.

Keep it straightforward:

This simple practice anchors the entire account in the witness's direct experience. There's no room for ambiguity about who is telling the story.

People naturally understand stories that unfold in chronological order. A judge, investigator, or jury will have a much easier time following an account that moves from one point in time to the next. Your template should guide the witness to think this way.

Start at the beginning of the event from the witness's perspective and move forward step-by-step. For an accident, the story might begin with what the witness was doing before the incident, then detail what they saw and heard during it, and finish with what happened immediately after. Breaking a complex event down into a clear sequence of smaller moments is the best way to avoid confusion.

The key is to recount events as they happened, without jumping back and forth in time. This simple discipline adds immense clarity and makes the account far more persuasive and easy to follow.

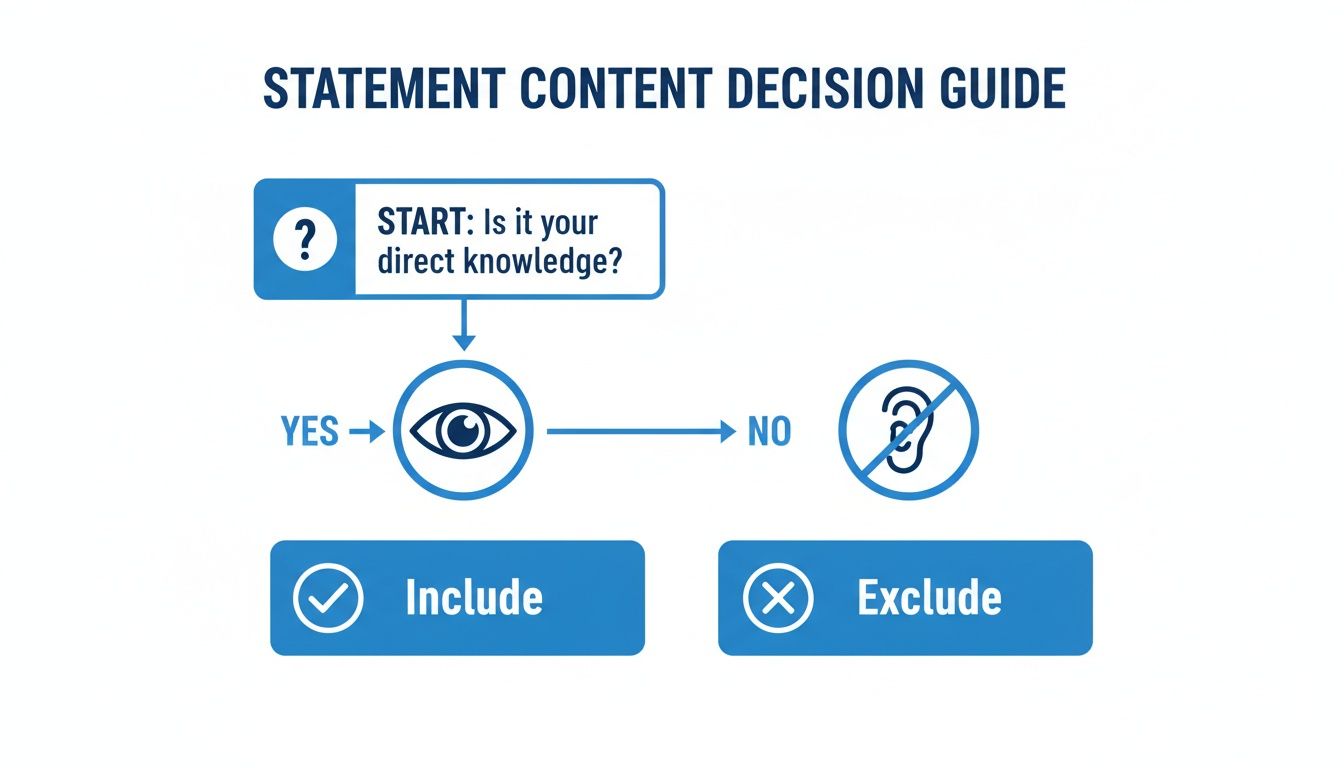

This is where many statements go wrong. It’s easy for a witness to slip from describing what happened to interpreting why it happened. The statement’s job is to present facts, leaving the conclusions to the lawyers and the court.

A witness should stick to what they observed with their senses, not what they think someone else was feeling or intending.

Here’s the difference:

The factual statement lets the reader draw their own conclusions from the evidence. If you're working from a recorded interview, using professional legal transcription services can help ensure you're capturing precise, verbatim facts.

Hearsay is a classic trap. It’s any information the witness didn't personally see or hear but was told by someone else. For instance, "My neighbor, John, told me he saw the delivery truck speeding" is pure hearsay. The witness didn't see it; they're just relaying what John said.

As a general rule, hearsay is inadmissible in court because it’s unreliable—you can’t cross-examine a memory of what someone else said. A witness statement must be confined to the witness's own sensory experiences. Including secondhand information can get entire sections of the statement thrown out. Our guide on https://www.legesgpt.com/blog/how-to-do-legal-research can offer more context on these evidence rules.

Authenticity is everything. A statement loaded with legal jargon or argumentative phrases immediately raises red flags. It suggests the account has been heavily shaped, or even written, by an attorney, which can tank the witness's credibility.

In high-stakes legal settings like the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), which heard from nearly 5,500 witnesses, a poorly structured or coached-sounding statement could completely undermine a witness's testimony. The lesson is clear: templates should guide, not dictate.

The best approach is to keep the language simple and the paragraphs short. Each paragraph should ideally focus on a single piece of information, making the narrative easy to scan and digest. Let the witness's genuine recollection shine through, unburdened by attempts to sound overly formal or strategically clever.

Don't fall into the trap of thinking a witness statement template is a one-size-fits-all document. What passes muster in a London civil court might be dead on arrival in a California criminal case. The legal world is a complex patchwork of different rules, and a good template needs to be flexible enough to adapt.

Ignoring these local variations isn't just a minor oversight—it can have serious consequences. A statement that disregards specific court rules on formatting, wording, or how to attach exhibits can be rejected outright. All that hard work? Wasted on a technicality.

That's why your first, non-negotiable step is always to check the local court rules or practice directions. Think of them as the official playbook for that specific jurisdiction. They lay out exactly what's required for your statement to be accepted.

While the heart of a witness statement—a factual, first-person account—is universal, the packaging can vary dramatically. You have to sweat the small stuff here, because getting the details right signals to the court that you understand and respect its procedures.

Here are a few common requirements that often change:

Beyond the aesthetics, the actual structure can shift. For instance, the introductory paragraph might need very specific phrasing to establish the witness's identity and role in the case according to local custom. Understanding these legal nuances is critical; you can learn more about what jurisdiction means in law to get a better handle on these concepts.

The Statement of Truth is probably the single most important part of the document to get right. This is the declaration at the end where the witness swears to the accuracy of their account. Its wording is almost always dictated by law or court rule and is absolutely not the place for creative writing.

For example, the language required in England and Wales under the Civil Procedure Rules is very precise and must include a stark warning about contempt of court. A U.S. federal court, on the other hand, will likely require a declaration "under penalty of perjury," using its own specific phrasing.

Simply grabbing a Statement of Truth from a generic online template is a huge mistake. You must find the exact wording required by the relevant court or tribunal and use it verbatim. This is non-negotiable.

Exhibits—the documents, photos, or other pieces of evidence mentioned in the statement—come with their own set of rules. Your template needs a clear and consistent system for referencing them, usually by assigning each one a unique identifier.

How you refer to them in the body of the text matters. You might write something like, "I then received the email, a copy of which is attached and marked as Exhibit A." The rules will also tell you how those exhibits need to be compiled, paginated, and physically attached to the statement. Getting this wrong can cause confusion and might even lead to a crucial piece of evidence being ignored.

At its core, though, the substance of the narrative follows one simple rule: stick to what you personally saw or did.

This flowchart neatly sums up the most fundamental rule of witness statements, a principle that holds true no matter the jurisdiction: hearsay is out.

To give you a practical sense of these differences, here’s a high-level comparison between the civil court systems in the UK and the US.

| Feature | United Kingdom (Civil Procedure Rules) | United States (Federal Rules of Civil Procedure) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Role | Often stands as the primary evidence-in-chief, reducing the need for lengthy oral testimony at trial. | Primarily used in pre-trial discovery (e.g., in support of motions) rather than as a substitute for live testimony. Witness testimony is typically given orally in court. |

| Statement of Truth | A very specific, mandatory declaration is required by CPR Part 22, including a warning about contempt of court. | Typically signed under penalty of perjury, often using phrasing like "I declare under penalty of perjury that the foregoing is true and correct." Wording can vary by state and federal court. |

| Hearsay | Generally inadmissible, but the statement must specify the source of any information and belief. | Hearsay rules are strict. Witness statements (affidavits/declarations) are often considered hearsay themselves and are only admissible under specific exceptions. |

| Exhibits | Referred to by the witness's initials followed by a number (e.g., "AB/1"). Exhibits are typically compiled in a separate, paginated bundle. | Often referred to as "Exhibit A," "Exhibit B," etc. They are attached directly to the affidavit or declaration. |

As you can see, even between two common law systems, the purpose and formal requirements of a witness statement can diverge significantly. Always verify the rules before you start drafting.

Even the most well-intentioned witness statement can be completely undermined by a few simple, common errors. After you’ve put in the work to draft the document, this final check is your quality control—your chance to catch and fix these pitfalls before they become a problem in a formal setting.

Think about it: a single poorly phrased sentence or an unverified detail can sow doubt where there should be clarity. Your goal is to produce a statement that is as solid, defensible, and factual as possible. The best way to achieve that is by understanding what not to do.

This is, without a doubt, the most frequent and damaging mistake I see. A witness's job is to state what they observed with their own senses—what they saw, heard, or did. It’s not their place to interpret those facts, guess at someone's intentions, or offer legal opinions.

For instance, a witness might write, "The driver was clearly negligent and driving recklessly." That’s an opinion and a legal conclusion. Determining negligence is the court's job, not the witness's.

The strong version presents concrete facts, allowing the reader to draw their own conclusions. Sticking to objective observations is the bedrock of a credible statement.

A statement's power lies in its factual purity. The moment a witness starts interpreting events or assigning motives, they cross a line from being an observer to being an advocate, which immediately weakens their testimony.

Precision is everything. Generalizations and vague descriptions make an account feel unreliable and hard to verify. Phrases like "a while later," "the car was going fast," or "he seemed angry" are just too subjective to hold up under scrutiny.

A strong witness statement template should prompt the user for specifics. Encourage the witness to be as concrete as possible.

Providing specific times, colors, locations, and descriptions anchors the statement in reality, making the account much more difficult to challenge.

A witness statement has to be a firsthand account. Period. Including information someone else told the witness—what's known in legal terms as hearsay—is a critical mistake. Hearsay is generally inadmissible in court because there's no way to cross-examine the original speaker to test the truth of their statement.

Here’s a classic example of what not to do:

Incorrect: "My coworker, Sarah, told me that she saw the manager shredding documents."

Unless the witness personally saw the manager shredding documents, that detail has no place in their statement. The only person who can truthfully testify to that event is Sarah. This is a non-negotiable rule to remember when learning how to write a witness statement template.

The final signature and the Statement of Truth are not just formalities—they’re what legally bind the witness to their account. A surprisingly common mistake is treating this step too casually.

The witness must read every single word of the final document to confirm it accurately reflects their memory. Any changes or corrections have to be made before they sign. An unsigned or improperly dated statement is essentially worthless in a legal context. On top of that, the exact wording of the Statement of Truth must comply with local jurisdictional rules to be considered valid.

Once you've got a draft in hand, you're on the home stretch. But this is often where the practical, real-world questions pop up. Even with a great template, you might run into issues with last-minute corrections or get tangled up in the signing process. Let's walk through some of the most common queries I hear from people finalizing their statements.

This is a great question, and it's a critical checkpoint. If you're reviewing the statement and a date is wrong, a detail is fuzzy, or there's even a simple typo—speak up immediately. It's your account, and it needs to be 100% accurate to your memory.

The person who drafted the document is responsible for making those changes. Don't feel pressured to sign anything until you've read it over and can honestly say, "Yes, this is my memory of what happened." Signing a statement with known errors, no matter how small, undermines its integrity.

Your signature on a witness statement is your solemn confirmation that the entire document is true to the best of your knowledge and recollection. It’s not a partial endorsement; it’s an all-or-nothing verification.

This is a trickier situation. Once a statement is signed and dated, it's considered a finished, formal document. You can't just go back and edit it with a pen or send a revised version.

The proper way to handle this is by preparing a second, supplementary witness statement. This new document would clearly state that it's an addendum to your first one (mentioning the date of the original) and then lay out the correction or additional information. It then gets signed and dated just like the first. This creates a transparent and honest record of how your evidence has evolved.

This completely depends on where you are and what the statement is for. The rules vary wildly.

For many civil cases in places like the UK, your own signature above the Statement of Truth is all that’s needed. No witness to the signature is required. However, in other contexts, especially with documents like affidavits or sworn declarations common in the US, you absolutely need an authorized person present. This might be a notary public or a solicitor.

It's important to understand they aren't witnessing the events you described—they're simply verifying your identity and witnessing the act of you signing the paper. Always, always check the specific rules for the court or tribunal you're dealing with. Getting this wrong can get your statement thrown out.

Yes, you absolutely should. Always request a final, signed copy for your own records. It’s not just for safekeeping; it’s a crucial tool.

If you're called to give evidence months or even years later, your memory might not be as sharp. Having your statement lets you refresh your recollection of the details exactly as you recorded them. Think of it as your personal, definitive record of what you told the court.

This is a simple one: tell the truth. And the truth is, "I don't know" or "I can't recall."

The biggest mistake a witness can make is guessing. Your credibility is everything. If you start speculating to fill in gaps—like the exact time something happened or the precise words someone used—you open the door to being discredited. It is far more powerful and believable to be honest about the limits of your memory. An account with a few "I'm not certain about that part" phrases often comes across as more authentic than one with an impossibly perfect memory.

Ready to create legally sound documents without the guesswork? LegesGPT offers an AI-powered legal assistant to help you draft, review, and research with confidence. Start your 3-day trial and see how much faster you can work.